Excerpt from The Orchard Is Full of Sound

Sheldon Lee Compton

I drove the first half of what would ultimately be a six-hour trip. During this drive, I forced Kenneth to be a springboard for ideas. First there was the business of introducing him to Breece to begin with.

“That’s a strange name,” he said.

“Well, it’s not as strange in certain areas of West Virginia,” I said. “You can look and find a ton of Pancakes in the phone book there.”

From there I moved on to all the proper highlights about Breece, covering a lot of ground far more quickly than I had imagined. Less than ten minutes, in fact. It struck me that there can be only so much to a life that lasted two and half decades. In the span of that short exchange, it became clear to me that Breece’s actual life wasn’t the real life left to us for discussion. His legacy, the one I needed to be talking with my brother about, was the twelve stories.

“He was from Milton?” Kenneth asked.

“Nevermind Milton,” I said. “But yes, he was from Milton. But never mind that right now. You need to read his story collection. That’s where you learn who Breece was. Where you learn who he still is to the people who care about his work.”

I noticed his gaze move toward the windshield, out beyond the two of us across some horizon or other, beyond yet another conversation about literature with his windbag brother.

“I’ve got the book right here on my phone. On my Kindle app on my phone,” I said. “They’re not the kind of stories I bet you’re thinking of. These go to some of the places we deal with, bub.”

“You want me to read? Now?”

He should have known the answer to that one.

I let him off the hook and asked that he read at least one story now. “I’ll be quiet and just drive. You read. Then we’ll talk.”

I had that feeling all writers would be familiar with, that kind of waiting that comes about when you’re anticipating what someone thinks about a story or book you wrote or recommended. And, also, this was the very definition of a crash course.

“What part you on?”

“Let’s see. He’s thinking about going on strike.”

“Good. Okay.”

It went like this for the next twenty minutes or so. He handed the phone back to me when he finished.

“Man, you ain’t kidding,” he said. “That last part was awesome. Biting the liver, all that detail. And that part with the bobcat watching for him to leave. I don’t know. Somehow that kind of summed up the whole thing.”

It was clear that Kenneth now had at least a slightly better understanding of what Breece was about. I kept taking the two-lane through Virginia in sweeping curves and Kenneth kept reading.

In Charlottesville, I switched seats with Kenneth. Driving in any town with a population larger than a few thousand means various roads I can’t seem to navigate to save my life. Even with Google Maps I would get twisted around. I thought to simply cut through all that and switch right up front. When he suggested seeing Monticello, I had to decline. This wasn’t a trip for sightseeing. I needed to get a hotel and then get to Blue Ridge Lane.

Hotel secured and still mid-afternoon, I insisted on a quick nap. Six hours in a vehicle meant my two back surgeries were taking center stage with my pain level. I never dream, but while falling asleep in that strange otherness that comes with every hotel room in the world, I focused on Buddy crouched there in the hills chewing liver like a madman about to do mad things and I focused on the bobcat waiting, surviving. I was the bobcat: Breece was the bobcat. At some point I finally collapsed into sleep.

I knew from the satellite mapping—those crisp, overhead images of 2215 Blue Ridge Lane and the surrounding neighborhood—that I had entered a residential section unlike anything Kenneth or I had ever been around. Homes listed by realtors for millions of dollars. Homes with garages bigger than any house he and I had ever lived in. Homes with parking lots instead of parking spaces. And as was the case with 2215 Blue Ridge Lane, swimming pools and guest houses. Guest houses big enough to rent to students.

During my time as a small-town journalist, not to mention my time as a pizza delivery driver, I knocked on a lot of doors in a lot of different places. Dangerous places. But the idea of swaggering up to the front door of this home and knocking was giving me the nervous chills. I was still on Farmington Drive leading into what I had already started referring to as the Country Club Section. The homes were, as Breece had said in his letters, in the middle of the golf course that was part of the Farmington Country Club. The very course he once did some work on for extra money. And then I turned right onto Blue Ridge Lane.

The moment was already surreal. More than a decade earlier I first pulled up Breece’s Wikipedia page and read about his short life, his suicide along a stretch of road in Charlottesville. Now I was on that road, and the very first right turn led to what was once the Meade home. The view from the satellite pictures did not do the place justice. A wide roadway that ended in a rounded left curve into what I’ve already described as a parking lot, one large enough to park a dozen vehicles. Larger than every single privately owned car lot I’d seen back in Kentucky.

There were no cars around. No sign that anybody was home and, for the first time since leaving for Charlottesville, it occurred to me that any number of scenarios could exist that would have the home empty. Work, vacation, currently on the market, visiting family out of state. But that didn’t really matter to me. I didn’t need to see the inside of 2215 Blue Ridge Lane; I needed only to stand in at least the general area where Breece left the world.

“Don’t look like there’s anybody home,” Kenneth said.

I had forgotten Kenneth was in the car. We both stepped out and shut our doors. “That’s about the luck I expected,” I said. “But you know, what I’m here for don’t really require a full tour.” As I said this, I pointed to a smaller path leading from the corner of the driveway nearest the main house. I knew from the maps that at the end of that path was a swimming pool and a guest house. The guest house.

“But we should knock at least, yeah?”

“We should knock, yes.”

I bypassed the small path leading to the guest house and found the front door of the main house. Or at least a door. For all I knew a house this big had any number of doors.

I knocked, then Kenneth knocked, and then I knocked again. Kenneth went to knock again and I stopped him, motioned to the guest house. “No signs I can see. We can always plead dumb, drop a thicker accent on them.”

Whoever had bought this home in 2017 for $4 million dollars was most certainly not here. Though I didn’t say it aloud, I was greatly relieved. Ever since calling Charlottesville several weeks before and trying to explain who Breece was, how he was significant to the great city, and having no luck, I wasn’t eager to talk with yet another person who likely had no idea how important he was to a large part of the literary community. And, worse, in this case the significance was literally in their backyard.

The look from Kenneth said volumes. Like a war cry he was saying, we’re low class, my brother, and low class never fairs all that good roaming around upper class property. The trip to the front door and back to the car was all I was going to have. Sure, I could return later that day, before bedding down at the hotel for the drive back the next morning. But that wasn’t going to happen. Once to the breech was enough. I knew Kenneth could feel the same thing I felt standing there in the middle of those luxury homes in the middle of that golf course in the land of Jefferson. He could feel that same tingling sensation across the skin, the old genetics letting us know we had wandered too far afield of our own land, our own people.

From where I stood the swimming pool was in view. I could see adjacent to that the guest house. Surely the space he rented. But left and right and in between there was no orchard. At once this melted something inside me.

“You know, I tried getting the police report.” I turned to Kenneth and waved my arm toward the parking lot and started the short walk away from the core of Breece’s legend. In the car, I settled back into the seat. “Yeah, I tried, but no luck. Called the city police. Their records stopped in 1997. Nothing else converted to the database before that. I tried the county. Worse luck there. Nothing before 1983. Even the division three post of the Virginia State Police said they had nothing that dated. It’s a long way back to 1979.”

Kenneth was quiet. I could feel the discomfort coming off him in those rings through time Breece so eloquently described. It was time to get back to our world. How often must Breece have felt the same way in this exact same place? How often must he have wished to be anywhere else but here? Then he left in his own way, and so did we.

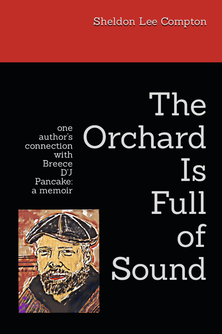

The Orchard Is Full of Sound, a new memoir about one author’s life and pursuit of closure for Breece D’J Pancake’s tragic death by Sheldon Lee Compton is now available from Cowboy Jamboree Press.

Sheldon Lee Compton

I drove the first half of what would ultimately be a six-hour trip. During this drive, I forced Kenneth to be a springboard for ideas. First there was the business of introducing him to Breece to begin with.

“That’s a strange name,” he said.

“Well, it’s not as strange in certain areas of West Virginia,” I said. “You can look and find a ton of Pancakes in the phone book there.”

From there I moved on to all the proper highlights about Breece, covering a lot of ground far more quickly than I had imagined. Less than ten minutes, in fact. It struck me that there can be only so much to a life that lasted two and half decades. In the span of that short exchange, it became clear to me that Breece’s actual life wasn’t the real life left to us for discussion. His legacy, the one I needed to be talking with my brother about, was the twelve stories.

“He was from Milton?” Kenneth asked.

“Nevermind Milton,” I said. “But yes, he was from Milton. But never mind that right now. You need to read his story collection. That’s where you learn who Breece was. Where you learn who he still is to the people who care about his work.”

I noticed his gaze move toward the windshield, out beyond the two of us across some horizon or other, beyond yet another conversation about literature with his windbag brother.

“I’ve got the book right here on my phone. On my Kindle app on my phone,” I said. “They’re not the kind of stories I bet you’re thinking of. These go to some of the places we deal with, bub.”

“You want me to read? Now?”

He should have known the answer to that one.

I let him off the hook and asked that he read at least one story now. “I’ll be quiet and just drive. You read. Then we’ll talk.”

I had that feeling all writers would be familiar with, that kind of waiting that comes about when you’re anticipating what someone thinks about a story or book you wrote or recommended. And, also, this was the very definition of a crash course.

“What part you on?”

“Let’s see. He’s thinking about going on strike.”

“Good. Okay.”

It went like this for the next twenty minutes or so. He handed the phone back to me when he finished.

“Man, you ain’t kidding,” he said. “That last part was awesome. Biting the liver, all that detail. And that part with the bobcat watching for him to leave. I don’t know. Somehow that kind of summed up the whole thing.”

It was clear that Kenneth now had at least a slightly better understanding of what Breece was about. I kept taking the two-lane through Virginia in sweeping curves and Kenneth kept reading.

In Charlottesville, I switched seats with Kenneth. Driving in any town with a population larger than a few thousand means various roads I can’t seem to navigate to save my life. Even with Google Maps I would get twisted around. I thought to simply cut through all that and switch right up front. When he suggested seeing Monticello, I had to decline. This wasn’t a trip for sightseeing. I needed to get a hotel and then get to Blue Ridge Lane.

Hotel secured and still mid-afternoon, I insisted on a quick nap. Six hours in a vehicle meant my two back surgeries were taking center stage with my pain level. I never dream, but while falling asleep in that strange otherness that comes with every hotel room in the world, I focused on Buddy crouched there in the hills chewing liver like a madman about to do mad things and I focused on the bobcat waiting, surviving. I was the bobcat: Breece was the bobcat. At some point I finally collapsed into sleep.

I knew from the satellite mapping—those crisp, overhead images of 2215 Blue Ridge Lane and the surrounding neighborhood—that I had entered a residential section unlike anything Kenneth or I had ever been around. Homes listed by realtors for millions of dollars. Homes with garages bigger than any house he and I had ever lived in. Homes with parking lots instead of parking spaces. And as was the case with 2215 Blue Ridge Lane, swimming pools and guest houses. Guest houses big enough to rent to students.

During my time as a small-town journalist, not to mention my time as a pizza delivery driver, I knocked on a lot of doors in a lot of different places. Dangerous places. But the idea of swaggering up to the front door of this home and knocking was giving me the nervous chills. I was still on Farmington Drive leading into what I had already started referring to as the Country Club Section. The homes were, as Breece had said in his letters, in the middle of the golf course that was part of the Farmington Country Club. The very course he once did some work on for extra money. And then I turned right onto Blue Ridge Lane.

The moment was already surreal. More than a decade earlier I first pulled up Breece’s Wikipedia page and read about his short life, his suicide along a stretch of road in Charlottesville. Now I was on that road, and the very first right turn led to what was once the Meade home. The view from the satellite pictures did not do the place justice. A wide roadway that ended in a rounded left curve into what I’ve already described as a parking lot, one large enough to park a dozen vehicles. Larger than every single privately owned car lot I’d seen back in Kentucky.

There were no cars around. No sign that anybody was home and, for the first time since leaving for Charlottesville, it occurred to me that any number of scenarios could exist that would have the home empty. Work, vacation, currently on the market, visiting family out of state. But that didn’t really matter to me. I didn’t need to see the inside of 2215 Blue Ridge Lane; I needed only to stand in at least the general area where Breece left the world.

“Don’t look like there’s anybody home,” Kenneth said.

I had forgotten Kenneth was in the car. We both stepped out and shut our doors. “That’s about the luck I expected,” I said. “But you know, what I’m here for don’t really require a full tour.” As I said this, I pointed to a smaller path leading from the corner of the driveway nearest the main house. I knew from the maps that at the end of that path was a swimming pool and a guest house. The guest house.

“But we should knock at least, yeah?”

“We should knock, yes.”

I bypassed the small path leading to the guest house and found the front door of the main house. Or at least a door. For all I knew a house this big had any number of doors.

I knocked, then Kenneth knocked, and then I knocked again. Kenneth went to knock again and I stopped him, motioned to the guest house. “No signs I can see. We can always plead dumb, drop a thicker accent on them.”

Whoever had bought this home in 2017 for $4 million dollars was most certainly not here. Though I didn’t say it aloud, I was greatly relieved. Ever since calling Charlottesville several weeks before and trying to explain who Breece was, how he was significant to the great city, and having no luck, I wasn’t eager to talk with yet another person who likely had no idea how important he was to a large part of the literary community. And, worse, in this case the significance was literally in their backyard.

The look from Kenneth said volumes. Like a war cry he was saying, we’re low class, my brother, and low class never fairs all that good roaming around upper class property. The trip to the front door and back to the car was all I was going to have. Sure, I could return later that day, before bedding down at the hotel for the drive back the next morning. But that wasn’t going to happen. Once to the breech was enough. I knew Kenneth could feel the same thing I felt standing there in the middle of those luxury homes in the middle of that golf course in the land of Jefferson. He could feel that same tingling sensation across the skin, the old genetics letting us know we had wandered too far afield of our own land, our own people.

From where I stood the swimming pool was in view. I could see adjacent to that the guest house. Surely the space he rented. But left and right and in between there was no orchard. At once this melted something inside me.

“You know, I tried getting the police report.” I turned to Kenneth and waved my arm toward the parking lot and started the short walk away from the core of Breece’s legend. In the car, I settled back into the seat. “Yeah, I tried, but no luck. Called the city police. Their records stopped in 1997. Nothing else converted to the database before that. I tried the county. Worse luck there. Nothing before 1983. Even the division three post of the Virginia State Police said they had nothing that dated. It’s a long way back to 1979.”

Kenneth was quiet. I could feel the discomfort coming off him in those rings through time Breece so eloquently described. It was time to get back to our world. How often must Breece have felt the same way in this exact same place? How often must he have wished to be anywhere else but here? Then he left in his own way, and so did we.

The Orchard Is Full of Sound, a new memoir about one author’s life and pursuit of closure for Breece D’J Pancake’s tragic death by Sheldon Lee Compton is now available from Cowboy Jamboree Press.